The Supreme Court of the United States recently affirmed the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission’s Order No. 745, on pricing for demand response (DR). At the core of the debate was the Commission’s decision to require wholesale markets to pay successful demand response bids the same Locational Marginal Price (LMP) paid to electricity generators. Professors William Hogan and the late Alfred Kahn, two giants among economists, squared off.

On one hand, I understand the logic behind my friend Bill Hogan’s arguments that the value of demand response to electricity buyers should be less than LMP, because the demand response product in this case is different than electricity purchased in the wholesale market, in that the latter can be resold to retail customers.

By contrast, Fred Kahn supported paying LMP to market participants that bid on products that reduce demand in wholesale electricity markets. Professor Kahn emphasized the importance of equating the marginal cost of electricity and the prices paid for products that provide measurable demand reduction.

In my initial comments on the FERC Notice of Proposed Rulemaking, I told the Commission that if external benefits were considered, then the marginal external benefits provided by demand response would prove more than sufficient to overcome Professor Hogan’s concerns that paying LMP was too expensive.

After weighing all the arguments (and there were many!), the Commission, under the leadership of chairman Jon Wellinghoff, eventually found a way to solve the conceptual debate between Hogan and Kahn. And so it designed the Final Order 745 with a demand response product that could be dispatched and sold as a supplement to the needs of those buying electricity in wholesale electricity markets.

How FERC Split the Difference

The Commission eventually found a way to reconcile Hogan with Kahn – by authorizing Regional Transmission Organizations (RTO) to dispatch demand-responsive resources at a price equal to full LMP, but only at those times when the RTO could determine that Demand-Side Management (DSM) would be cost-effective. To enable that solution, the Commission required a specific net-benefits test (NBT) to determine cost-effectiveness.

This test requires that the price reduction that comes from dispatching DSM (i.e., the difference between the initial or ex ante LMP and the new or ex post LMP, after dispatching DSM) must exceed the amount paid to compensate successful DSM providers. In this way the NBT would ensure that all buyers, collectively, would pay less.

Thus, under FERC’s rule, the market compensates DSM providers with the new LMP (that generators receive when dispatched by the market), but only when the new LMP plus the DSM cost recovery adder would be less than the old LMP.¹ The estimated savings would pay to secure the verified and measured demand reduction that lowers electricity prices. In effect, the FERC adopted what many call a “hold harmless” test as a requirement for including demand response supplements in wholesale electricity markets.

I recognize that generation owners, who supply the market with electricity, would prefer a higher price for their output. Regardless, the NBT ensures that those buyers that are ultimately assigned the cost of the demand response fees are either better off or indifferent.

Thus, neither the FERC nor the Supreme Court majority relied on external benefits to reach their shared conclusion – that all buyers would be better off (or at least no worse off) if all buyers paid the lower ex ante LMP, plus the price of the DR product that reduced demand and thus lowered the market price. This is important because state regulators now can continue to use external benefits to establish appropriate state energy efficiency programs without any concern that the external benefits are counted twice.

Also, Order 745 supports the emergence of demand-side aggregators for small electricity users and encourages larger commercial users to become more efficient. Retail energy efficiency or conservation results in end-users buying less electricity.

But that is not the same thing as offering a load control or demand response that the RTO can dispatch and manage through load control. Rather, under Order 745, it is this new dispatchable load control or demand response that becomes the actual product or service. Order 745 thus allows this product to be sold in wholesale markets if the conditions support a positive NBT result.

Where We Go From Here

State regulators today have mostly completed the task of balancing the interests of consumers, shareholders, and customers who participate in utility-sponsored energy efficiency programs. But Order 745 will extend the application of load-reducing technologies and marketing to a new class of services. The rule will allow wholesale markets to shape load curves to reduce the prices, while providing financial incentives for market participants to offer to sell demand- or load-management in increments that can be dispatched.

The ultimate consequence or effect of Order 745 will likely not end with wholesale markets. Digital technology exists to convert virtually every device in a home or business so that it is capable of being controlled.

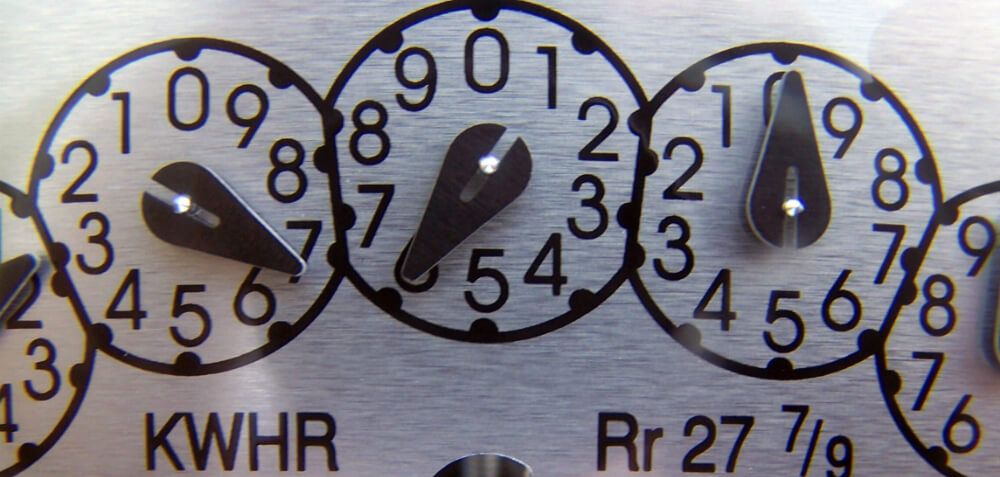

Regulated utility companies are adding smart meters that can become control central for accessing and aggregating retail customers’ electricity use and the timing of that use.

These smart meters mark an important dividing line, with utilities on one side and customers and their devices on the other.

Change threatens utility sales of electricity and tempts other businesses to invade the valuable space on the customers’ side of the meters. Privacy is not unimportant or a distraction.

Some states already are grappling with who can enter this space and what rules of the road will prevail. Order 745 opens the vast potential of wholesale markets and value of the transactions in these markets to be used to help finance, leverage, and incentivize retail customers and state regulators to solve the challenging tariff, competition, and customer protection issues. State regulators will have much to say and Order 745 opens more opportunities than it closes.

Endnote:

1. The details are explained in Brief of Amicus Curiae Charles J. Cicchetti in Support of Petitioners, Supreme Court of the United States, Federal Energy Regulatory Commission v. Electric Power Supply Association, et al., Nos. 14-840 & 18-841, pages 14-16.